“We can do things differently to reinvent growth without pollution. But only if we have the courage to think differently.” – Sunita Narain in Down To Earth >>

In the Washington Post [22 November 2017], Kevin Gover, director of the museum, deals with five popular misconceptions about Native America | Read the full story here>>

Thanksgiving recalls for many people a meal between European colonists and indigenous Americans that we have invested with all the symbolism we can muster. But the new arrivals who sat down to share venison with some of America’s original inhabitants relied on a raft of misconceptions that began as early as the 1500s, when Europeans produced fanciful depictions of the “New World.” In the centuries that followed, captivity narratives, novels, short stories, textbooks, newspapers, art, photography, movies and television perpetuated old stereotypes or created new ones — particularly ones that cast indigenous peoples as obstacles to, rather than actors in, the creation of the modern world. I hear those concepts repeated in questions from visitors to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian every day. Changing these ideas is the work of generations. Here are five of the most intransigent.

MYTH NO. 1 There is a Native American culture.

This concept really took hold when Christopher Columbus dubbed the diverse indigenous inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere “Indians.” Lumping all Native Americans into an indiscriminate, and threatening, mass continued during the era of western expansion, as settlers pushed into tribal territories in pursuit of new lands on the frontier. In his 1830 “Message to Congress,” President Andrew Jackson justified forced Indian removal and ethnic cleansing by painting Indian lands as “ranged by a few thousand savages.” But it was Hollywood that established our monolithic modern vision of American Indians, in blockbuster westerns — such as “Stagecoach” (1939), “Red River” (1948) and “The Searchers” (1956) — that depict all Indians, all the time, as horse-riding; tipi-dwelling; bow-, arrow- and rifle-wielding; buckskin-, feather- and fringe-wearing warriors.

Yet vast differences — in culture, ethnicity and language — exist among the 567 federally recognized Indian nationsacross the United States. It’s true that the buffalo-hunting peoples of the Great Plains and prairie, such as the Lakota, once lived in tipis. But other native people lived in hogans (the Navajo of the Southwest), bark wigwams (the Algonquian-speaking peoples of the Great Lakes), wood longhouses in the Northeast (Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois peoples’ name for themselves, means “they made the house”), iglus and on and on. Nowadays, most Native Americans live in contemporary houses, apartments, condos and co-ops just like everyone else.

There is similar diversity in how native people traditionally dressed; whether they farmed, fished or hunted; and what they ate. Something as simple as food ranged from game (everywhere); to seafood along the coasts; to saguaro, prickly pear and cholla cactus in the Southwest; to acorns and pine nuts in California and the Great Basin.

MYTH NO. 2 American Indians get a free ride from the U.S. government.

The notion that indigenous people benefit from the government’s largesse is widespread, according to “American Indians: Stereotypes and Realities,” by Choctaw historian Devon Mihesuah. Staff and volunteers at our Washington and New York museums hear daily about how Washington “gave” Native Americans their reservations and how the Bureau of Indian Affairs manages their lives for them.

The fight for Native American humanity

In 1879, a landmark case asked the question: Are Native Americans considered human beings under the U.S. Constitution? This is Chief Standing Bear’s story. (The Washington Post)

But Native Americans are subject to income taxes just like all other Americans and, at best, have the same access to government services — though often worse. In 2013, the Indian Health Service (IHS) spent just $2,849 per capita for patient health services, well below the national average of $7,717. And IHS clinics can be difficult to access, not only on reservations but in urban areas, where the majority of Native Americans live today.

As for reservations, most were created when tribes relinquished enormous portions of their original landholdings in treaties with the federal government. They are what remained after the United States expropriated the bulk of the native estate. And even these tenuous holdings were often confiscated and sold to white settlers. The Dawes Allotment Act, passed by Congress in 1887, broke up communally held reservation lands and allotted them to native households in 160-acre parcels of individually owned property, many of which were sold off. Between 1887, when the allotment act was passed, and 1934, when allotment was repealed, the Native American land base diminished from approximately 138 million acres to 48 million acres.

MYTH NO. 3 ‘Native American’ is the proper term.

Commentaries and corporate guidelines address the notion that “Native American” is preferred or that “American Indian” is impolite. During the 1492 quincentennial, Oprah Winfrey devoted an hour of her show to the subject. At the museums and on social media, people ask at least once per day when we are going to take “American Indian” out of our name.

The term Native American grew out of the political movements of the 1960s and ’70s and is commonly used in legislation covering the indigenous people of the lower 48 states and U.S. territories. But Native Americans use a range of words to describe themselves, and all are appropriate. Some people refer to themselves as Native or Indian; most prefer to be known by their tribal affiliation — Cherokee, Pawnee, Seneca, etc. — if the context doesn’t demand a more encompassing description. Some natives and nonnatives, including scholars, insist on using the word Indigenous, with a capital I. In Canada, terms such as First Nations and First Peoples are preferred. Ditto in Central and South America, where the word indio has a history of use as a racial slur. There, Spanish speakers tend to use the collective word indígenas, as well as specific national names.

MYTH NO. 4 Indians sold Manhattan for $24 worth of trinkets.

This myth — repeated in textbooks and made vivid in illustrations — casts Native Americans as gullible provincials who traded valuable lands and beaver pelts for colorful European-made beads and baubles. According to a letter to Dutch officials, the settlers offered representatives of local Lenape groups 60 guilders, about $24, in trade goods for their homeland, Manahatta. The best insight we have into what the Lenape received comes from a later 17th-century deed for the Dutch purchase of Staten Island, also for 60 guilders, which lists goods “to be brought from Holland and delivered” to the Indians, including shirts, socks, cloth, muskets, bars of lead, powder, kettles, axes, awls, adzes and knives. The Dutch recognized the mouth of the Hudson River as a gateway to valuable fur-trapping territories farther north and west.

But it is unlikely that the Lenape saw the original transaction as a sale. Although land could be designated for the exclusive use of prominent native individuals and families, the idea of selling land in perpetuity, to be regarded as property, was alien to native societies. Historians who try now to reconstruct early transactions between Europeans and Native Americans differ over whether the Lenape considered it an agreement for the Dutch to use, but not own, Manahatta (the majority view), or whether even as early as 1626, Indians had engaged in enough trade to understandEuropean economic ideas.

MYTH NO. 5 Mascots honor Native Americans.

Many people, including some American Indians , hold that naming sports teams after Native American caricatures, such as the Redskins and the Braves, recognizes the strength and fortitude of native peoples. “It represents honor, represents respect, represents pride,” Redskins owner Dan Snyder told ESPN.

A little history: The use of Native Americans as mascots arose during the allotment period, a time when U.S. policy sought to eradicate native sovereignty and Wild West shows cemented the image of Indians as plains warriors. (No wonder all of these mascots resemble plains Indians, even when they represent teams in Washington, Florida and Ohio.)

What’s more, social science research suggests not only that some native people recognize the word “Redskins” as a racial slur and are offended by it, but that exposure to mascots and other stereotypes of Native Americans has a negative impact on American Indian young people. According to a study by Tulalip psychologist Stephanie Fryberg, such mascots “remind American Indians of the limited ways others see them and, in this way, constrain how they can see themselves.” Likewise, in 2005, the American Psychological Association called for the retirement of all Indian mascots, symbols and images, citing the harmful effects of racial stereotyping on the social identity and self-esteem of American Indian youth.

Kevin Gover, a citizen of the Pawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, is the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Follow @SmithsonianNMAI

Twitter: @SmithsonianNMAI

Five myths is a weekly feature challenging everything you think you know. You can check out previous myths, read more from Outlook or follow our updates on Facebook and Twitter.

Source: The Washington Post, Outlook Perspective, 22 November 2017 https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/five-myths/five-myths-about-american-indians/2017/11/21/41081cb6-ce4f-11e7-a1a3-0d1e45a6de3d_story.html?utm_term=.74433ae99341

Date accessed: 11 December 2017

“I would like to direct attention to the general approach when we encounter the ‘other’ – the question of our protocol, etiquette and attitude. In our eagerness to know we probably show a disregard to these civilities. We try to buy friendship for building up rapport; we try to intrude into others’ territory without being invited and carry presents that we perceive would be appreciated to assert our friendliness.” – Anthropologist R.K. Bhattacharya in “The Holistic Approach to Anthropology” >>

COVID-19 in Indian Country

Native Americans and Alaska Natives throughout the United States have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic—across all age groups. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases among Native Americans and Alaska Natives was 3.5 times higher than among the general population.

Native peoples in the United States have had the highest hospitalization rate among any racial and ethnic group in the country. There are multiple historic reasons for this. Most critically, Native Americans and Alaska Natives have higher rates of underlying chronic diseases than the general U.S. population. This health care crisis is, in no small measure, due to the failure of the United States to live up to its treaty obligations to Native Nations.

The United States signed a series of treaties with Native Nations, making promises in exchange for parts, or the entirety, of their sovereign territories. The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized these treaties as legally binding. The unmet treaty rights have contributed to enormous health disparities between Native Americans and the general U.S. population, including a lack of access to well-equipped and staffed medical facilities.

Source: “COVID-19 in Indian Country” (National Museum of the American Indian in Washington)

URL: https://americanindian.si.edu/developingstories/quintero.html

Date Visited: 4 September 2021

55 Voices for Democracy: “Bolder Reimagining” by Alexandra Kleeman

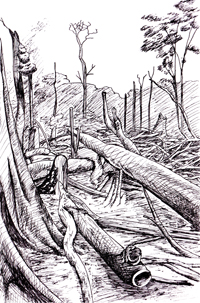

“A man named Hoodoo went on one of the last buffalo hunts in the Cimarron country. […] Hunters equated buffalo with the indigenous tribes of the region, and made war on the animal, as they made war on the people of the plains, to weaken the people and erode their way of life. […]

Today, some scientists estimate that we are living in a “10 percent world” — a world reduced to just 10 percent of its past abundance of nonhuman life. And a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimates that just four percent of the planet’s biomass is now made up of wild animals — Humans account for 36 percent and their livestock for an additional 60 percent.

How is this loss made manifest in our everyday lives?

Many of us have our own stories about a place we once loved that has since been transformed into a housing development or strip mall, a bird or insect or wild animal that we used to see that we haven’t seen in years. But we tend to think of these experiences as personal, rather than part of a greater shared loss, a gradual reduction of world. This loss is already present in our lived experience, but just as the violence it signifies is done out of our line of sight — displaced temporally and spatially — its phenomenology makes it difficult to perceive, easier to hide or to ignore. It saps the potentiality of the world in an insidious way, quietly subtracting while leaving intact a sense of continuity. In this way the realm of possibility, that space in which we maneuver both politically and socially, constricts around us. […]

Already, activists working with the movement have succeeded in dismantling dams and returning lands near Big Sur to the formerly unlanded Essalen tribe. As I speak to you today from present-day Los Angeles County, the ancestral lands of the Tongva, Chumash, and Kizh tribes, I’m reminded that this region now called California was once home to an estimated 350,000 indigenous lives, a complex array of civilizations decimated by colonization and American expansion. If it was possible for the land they stewarded to be violently taken by newcomers, isn’t it possible to peacefully return it, to make reparations for what was taken? In the past, and in our reckoning with loss, lies a world-expanding vision of the future, one that is not only possible but necessary.

*

“55 Voices for Democracy” is inspired by the 55 BBC radio addresses Thomas Mann delivered from his home in California to thousands of listeners in Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, and the occupied Netherlands and Czechoslovakia between October 1940 and November 1945. In his monthly addresses Mann spoke out strongly against fascism, becoming the most significant German defender of democracy in exile. Building on that legacy, “55 Voices” brings together internationally esteemed intellectuals, scientists, and artists to present ideas for the renewal of democracy in our own troubled times. The series is presented by the Thomas Mann House in partnership with the Los Angeles Review of Books, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Deutschlandfunk.

Source: “Bolder Reimagining” by Alexandra Kleeman (55 Voices for Democracy: “Bolder Reimagining” by Alexandra Kleeman, 31 December 2021)

URL: https://blog.lareviewofbooks.org/55-voices/55-voices-democracy-bolder-reimagining-alexandra-kleeman/

Date Visited: 12 January 2022

[Bold typeface added above for emphasis]

“In India, the term ‘tribe‘ has referred, since the 16th century, to groups living under ‘primitive‘ and ‘barbarous‘ conditions. The colonial administration used the term to distinguish peoples who were heterogeneous in physical and linguistic traits and lived under quite different demographic and ecological conditions, with varying levels of acculturation and development. In the various countries of South Asia, tribal peoples were often called by derogatory terms such as jungli (‘savage’) during the colonial period.” – Marine Carrin, General Introduction to Brill’s Encyclopedia of the Religions of the Indigenous People of South Asia >>