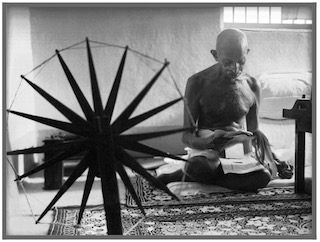

Perhaps no one grasped this dimension of colonialism as sharply and instinctively as Mahatma Gandhi, who chose khadi as his non-violent tool to advance the cause of India’s freedom. The humble handspun and handwoven fabric was a revolutionary emblem of the political fight for Indian independence, and an equally important revitalising instrument in the Gandhian toolkit to make the villages self-sufficient and uplift the poorest.

Neeta Deshpande in “India at 75: Khadi was an integral part of the freedom struggle. Where is handspun fabric today?”, Scroll.in | Gandhian social movement >>

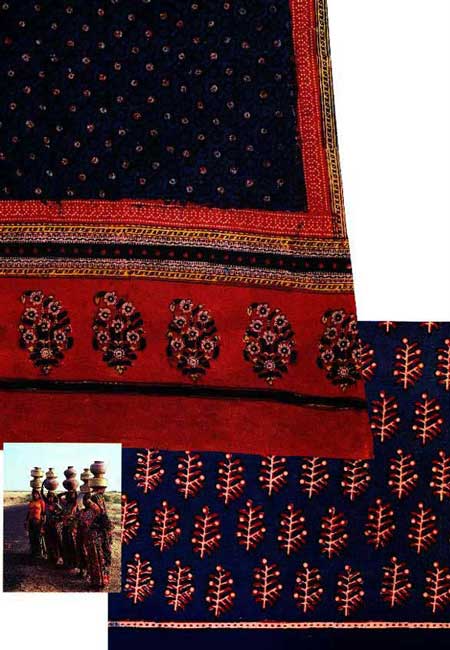

The western region consists of the desert states of Gujarat and Rajasthan as well as Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh and western Madhya Pradesh. […]

The region is home to a wide variety of people with different religions and cultures, most of whom have distinctive traditional textiles. They include Jains, Parsis, Hindus and Muslims, as well as tribal groups such as the Bhils and Mina. Yet the dominant characteristic of the traditional saris and odhnis of all these communities, as with all western Indian fabrics, is colour. For textile variation in the western region is determined by dyeing rather than weaving techniques, and the three major forms of Indian resist-dyeing evolved here. These are block-printing, tie-dye, and ikat, which culminates in the complex multicoloured patola. […]

This region’s propensity toward colour has deep roots, for it is here that the Indus Valley civilization developed cotton-growing and -dyeing technologies. From at least the early second millennium AD, western India has traded dyed textiles to the Middle East, South-East Asia and the Far East, and later to Europe and the Americas, although most local communities maintained their own textile designs. These usually had Mughal-style or geometric patterns, unlike those created in export cloths. Today, however, modern saris are often created using the resist-dyed saudagiri (trade cloth) prints once made solely for the foreign market.

Source: Lynton, Linda. The Sari: Styles, Patterns, History, Techniques. London: Thames and Hudson, 1995, p. 25.

Fig. 29-31, Photos: Sanjay K. Singh *

* Fig. 29 Above The fact that the traditional designs of many Bhil saris are in the Mughal style shows how well entrenched the Mughal aesthetic is in the western region. Elsewhere in India, most tribal and ethnic saris do not carry this type of pattern. Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 1954.

Learn more about textiles and ornaments associated with tribal communities >>

[C]aste Hindu society in India is so convinced of its own superiority that it never stops to consider the nature of social organisation among tribal people. In fact it is one of the signs of the ‘educated’ barbarian of today that he cannot appreciate the qualities of people in any way different from himself – in looks or clothes, customs or rituals.

“Hands off tribal culture” (Commentary), India Today, 9 January 2014

URL: https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/guest-column/story/19800915-hands-off-tribal-culture-821415-2014-01-09

Date Accessed: 27 July 2021

The Union Government amended the Flag Code of India in December 2021 to allow the manufacture of polyester and machine-made national flags. Ever since independence, Indians flags were required to be made from khadi – that is, handwoven from handspun cotton, silk, or wool yarn. The recent amendment is purportedly meant to increase the availability of flags for the government’s “Har Ghar Tiranga” programme to celebrate 75 years of Indian independence.

However, this move betrays the cherished values of our freedom struggle, which was fought with khadi as a symbolic inspiration. As we will see, this repudiation of khadi also encapsulates how successive governments in independent India have effectively worked to destroy the much larger handloom sector whose ambit extends well beyond khadi. […]

The amendment to the flag code is but a reflection of the twinned policy choices which have steered the development of the textile sector. The first of these is the decisive push for powerlooms – machines to manufacture fabric – which displaced massive numbers of handloom and khadi weavers from their means of livelihoods. Handloom fabric is handwoven from industrial yarn, while khadi fabric is handwoven from handspun yarn, and handloom and khadi operate in distinct spheres.

The second, equally important policy choice in the textile sector was the facilitation of the rapid advance of polyester in lieu of cotton – which impacted cotton farmers, as well as handloom weavers most of whom worked with cotton. In a nutshell, these coupled developments further impoverished millions of rural workers. Not to mention the environmental impacts of industrial textile manufacture which are well understood. […]

Indian cottons go back five millennia. Stories of how they travelled far from our borders in ancient times are legion. Large volumes of Indian textiles were sold regularly in the Indian Ocean region from at least the twelfth century. And after the arrival of Europeans in the subcontinent, Indian cotton fabric was the kingpin of manufactured goods in world trade from the sixteenth century up until the industrialisation of Europe.

Come British rule and following the Industrial Revolution, India lost its dominant position in the global trade of cotton textiles. By exploiting India and other colonies as well as British workers, Britain emerged as the main player, flooding the world with its mill-made cloth. In this process India was remoulded as a supplier of raw cotton for British mills and, crucially, the world’s biggest market for the products of those mills. Not surprisingly, the destruction of India’s handloom industry in the colonial period became a cornerstone of the Indian indictment of the Raj.

Rajghat, New Delhi-110002

Spinning Wheel Gallery >>

Related posts: Gandhian social movement >>

Perhaps no one grasped this dimension of colonialism as sharply and instinctively as Mahatma Gandhi, who chose khadi as his non-violent tool to advance the cause of India’s freedom. The humble handspun and handwoven fabric was a revolutionary emblem of the political fight for Indian independence, and an equally important revitalising instrument in the Gandhian toolkit to make the villages self-sufficient and uplift the poorest.

The Nehruvian state effectively rejected khadi and handloom, setting its mind on industrial and mechanised production. This was a continuation of the colonial era policies that, undergirded the explosive growth of British mills at the cost of Indian hand production. […]

When India became free, the fledgling democracy faced a mountain of diverse challenges. An exploitative colonial regime had left the new nation in a quagmire of economic underdevelopment and widespread poverty. As mentioned earlier, at the time the handloom sector was the second-largest source of rural employment after agriculture. Therefore, the story of this sector highlights the fate of the countryside and that of large numbers of ordinary Indians through the seventy-five years of India’s journey as an independent nation.

A close look at textile policy offers insights. Though some policy measures including the institution of handloom cooperatives have proven to be beneficial to a limited extent, the larger picture is extraordinarily bleak.

Handloom weavers – as well as powerloom and mill workers – have always been underpaid, overworked, and compelled by their circumstances to live and labour in poor conditions. To make a long story short, the thrust of textile policies has been to privilege production and profits over the ordinary producer at the bottom of the ladder. One of the main policy planks to achieve this end was to back the phenomenal growth of electricity-driven powerlooms. […]

For every job created in the powerloom sector, fourteen handloom weavers were displaced. With the advance of technology, a much more sophisticated powerloom today displaces that many more. […]

Nowadays it is getting increasingly difficult to find pure cotton garments for purchase, as corporations have flooded the market with cheap polyester and its blends with cotton. This is not only because of consumer preference for polyester, which is considered to be more convenient and affordable than cotton. Crucially, the transition to synthetics has been aided by the government’s policies in the liberalisation era, which in turn were influenced by the synthetic fibre industry. […]

The long road traversed by the Indian handloom sector has thus left a sad record of the consequences of the country’s policy choices for human welfare. According to textile ministry reports, powerlooms account for 60% of cloth production in the country today, while the share of handlooms is 15%. But the handloom production statistics are grossly inflated. With the secular decline of the sector, its production is a small fraction of the official figure, which points to the extent of displacement in the sector. Having to leave their looms idle, skilled weavers are reduced to manual labour as construction workers or farmhands, if at all such work is regularly available.

In this way, India’s once-famed artisans, who were impoverished in the colonial period, have also been failed by our own governments. Ironically, through policies which marginalised the handloom sector, successive governments of India have managed to achieve what the British could not fully accomplish. […]

A case in point is the 1980 Report of the Expert Committee on Tax Measures to Promote Employment of the Finance Ministry, according to which “the per unit employment in the [textile] mill industry is 9.1% of [that] in the handloom industry”. Thus, if only early textile policy had supported and protected the handloom sector, it could have provided meaningful work to a significant extent in the countryside. Instead, a developing India relegated its rural citizenry to the economic margins time and again.

Apart from this human story, the environmental damage caused by industrial textile production is no less staggering, with fast fashion today adding fuel to the fire. In parallel, the story of the cotton farming economy – which provides the raw material for cotton textile production – is also one of putting production on a technology treadmill while ignoring the plight of farmers. […]

The agrarian economy is in a shambles today, with a dearth of alternative livelihood opportunities available for these artisans. Regardless of the position one takes on industrialisation or the nature of development we should pursue, the question 75 years after independence remains – what happens to them?

Neeta Deshpande is working on a book on the handloom industry and cotton farming in modern India. She is a Fellow of the New India Foundation.

Source: “India at 75: Khadi was an integral part of the freedom struggle. Where is handspun fabric today?” by Neeta Deshpande, Scroll.in, 14 August 2022

URL: https://scroll.in/article/1030276/india-at-75-khadi-was-an-integral-part-of-the-freedom-struggle-where-is-handspun-fabric-today

Date Visited: 18 August 2022

“Bapuji ki Amar Kahani”, the Immortal Story of Bapuji | Learn more >>

Related posts: Gandhian social movement >>

‘Har Ghar Tiranga’: The Heart, the State, and the Indian Constitution

On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of Indian independence, August 15

By Vinay Lal, Posted on August 16, 2022 | Read the full article here >>In the wake of the “Har Ghar Tiranga” campaign, a campaign designed to encourage every Indian home (har ghar) to display the National Flag (tiranga, literally tri-colored), it is useful to think briefly about the evolution of the national flag, its place in the nationalist imagination during the anti-colonial struggle, and the particular way our relationship to the flag is a matter of the heart, the state, and the Indian constitution. Some people have thought that the orange in the flag represents the Hindu constituency, the green the Muslim community, and that all “others” are represented by the white in the flag. Gandhi had said as much, in an article for Young India on 13 April 1921, except that at that time red took the place of orange, but he also added that the charkha or spinning wheel in the middle of the flag pointed both to the oppressed condition of every Indian and simultaneously to the possibility of rejuvenating every household. The Constituent Assembly debates, which led to the adoption of the tricolored flag on 22 July 1947, suggest that some members were more inclined towards another interpretation, seeing the green as a symbol of nature and the fact that we are all children of ‘Mother Earth’, the orange as symbolizing renunciation and sacrifice, and white as symbolic of peace (shanti). That may be so, but the tiranga cannot be unraveled without some consideration of how it emerges from the three-forked road of the heart, the state, and the constitution.

Just what, however, is a national flag and why do all nation-states have one? The national anthem and the national flag are the bedrock of every nation-state; nearly all also have a national emblem, as does India. India has a complicated history around the national anthem, “Jana Gana Mana”, and the country officially also has a national song, “Vande Mataram”; and, then, there is an unofficial anthem, “Saare Jahan Se Accha”, which has wide currency. This makes the national flag especially and supremely important in India as an unambiguous marker of the nation-state. The honor and integrity of the nation are supposed to be captured by the flag, and the narrative of the nation-state everywhere offers ample testimony that the national flag is uniquely capable of enlisting the aid of citizens, giving rise to sentiments of nationalism, and evoking the supreme sacrifice of death. In a multi-ethnic, multi-religious, and highly polyglot nation such as India, the national flag is there to remind every Indian that something unites them: before their allegiance to a language, religion, caste group, or anything else, they are Indian. Thus, in every respect, the national flag commands, not merely our respect, but our allegiance to the nation. […]

If Indians fought for the national flag with zeal, they did so because they believed in what it stood for and they did so from their own volition against colonial oppression. The affection for the flag came from within, as a mandate from the heart rather than from the state. […]

That larger right to freedom of speech and expression which subsumes the right to fly the flag is critically important, but it is also equally important to recognize that the Constitution, as the supreme law of the land, itself subsumes the National Flag. Now that the citizens of India have won the right to hoist the National Flag without restriction, consistent with respect to the National Flag, it is perhaps time to think about the corresponding duty they owe to respect the freedom of speech and expression, and the obligation, which the present government has shown little if any interest in honoring, to protect the Fundamental Rights promised in the Constitution to every citizen.

Source: by Vinay Lal (Professor of History & Asian American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles UCLA)

URL: https://vinaylal.wordpress.com/2022/08/16/har-ghar-tiranga-the-heart-the-state-and-the-indian-constitution/

Date Visited: 18 August 2022

[Bold typeface added above for emphasis]

Find publications by reputed authors (incl. Open Access)

Learn more

Crafts and visual arts | Fashion and design | Masks

eBooks, eJournals & reports | eLearning

eBook | Background guide for education

Forest dwellers in early India – myths and ecology in historical perspective

Himalayan region: Biodiversity & Water

History | Hunter-gatherers | Indus Valley | Megalithic culture | Rock art

Languages and linguistic heritage

Modernity | Revival of traditions

Tribal Research and Training Institutes with Ethnographic museums